Social and Emotional Development In the Home

A child’s home influences his or her development. The home is a safe place for play and nurturing, which is key for social and emotional development. The home is also where important interactions happen with parents, caregivers, friends, siblings, and others in the community.

This chapter focuses on the home environment and how positive interactions between parents and children can support healthy social and emotional development in early childhood. It also describes parental stress and parental mental health concerns in more detail. Both are significant influences on the social and emotional well-being of children, and help and support are available for both. This chapter concludes with a discussion of social support, which was touched on in Chapter Two.

Parent-child Interactions Affect Social and Emotional Development.

A child’s relationship with a consistent, caring adult in the early years is associated with healthier behaviors, more positive peer interactions, increased ability to cope with stress, and better school performance later in life 17. Babies who receive affection and nurturing from their parents have the best chance of healthy development.

Figure 3.2 shows the proportion of parents who did not engage with their children in different activities that support positive parent-child interactions and social and emotional development of the child. Nationally, 15–20 percent of parents are not regularly engaging in these activities with their children.

Source: National Household Education Surveys (NHES) Program Public-Use Data File, Early Childhood Program Participation, 2005. U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics

Did you know?

- Parental warmth—touching, holding, comforting, rocking, singing, and talking calmly—can help children manage their emotional experience. This can contribute to the reduction of behavior problems down the road 27.

Parental Stress may Hinder the Social and Emotional Development of Children.

The developing brains of infants and toddlers are wired to expect responsive, warm, and sensitive interactions with parents and caregivers. But if that doesn’t happen, children can suffer. Children in families experiencing hardship or poverty often witness stress, in the form of sadness and anger, from their parents and don’t get the nurturing they need 28. This can affect children’s abilities to understand and read people’s emotions 28. Children as young as two can also experience sleep disturbances, become withdrawn, or display aggressive behaviors 29. These and other negative behaviors can follow them into later childhood and adulthood.

Data facts:

- In a national study of high-risk children in Early Head Start, approximately 28% of parents with children 12 months old report having high levels of parental stress 12.

- Using the same measure, approximately 15% of parents with children 12 months old in Shelby County report having high levels of parental stress.

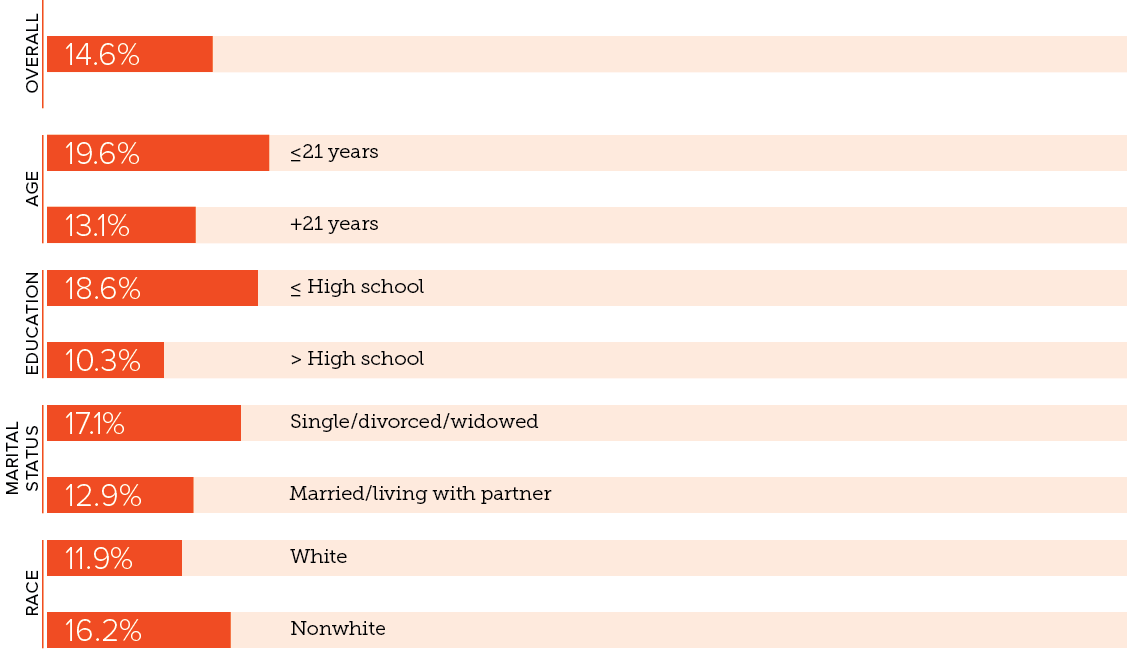

- Mothers who are younger, single, have lower education levels, or are nonwhite are more likely to report having high levels of parental stress (Figure 3.3).

Source: CANDLE Study (2009–2014) Parenting Stress Index (PSI) , percentage who met cutoff (>31) score for parental distress subscale

Maternal or Paternal Depression may Harm Parent-child Interactions.

Parental depression also poses a serious risk for healthy child development.

If a parent has depression, he or she is less likely to provide rich, positive experiences that promote healthy social and emotional development. It can also compromise the quality of the parent–child relationship during critical years of development 30-34.

Data facts:

- In the first year following childbirth, 7 percent to 13 percent of women experience depression 35.

- In a national study of high-risk children in Early Head Start, 17.6 percent of mothers of 12-month-olds experienced moderate to severe depression 36.

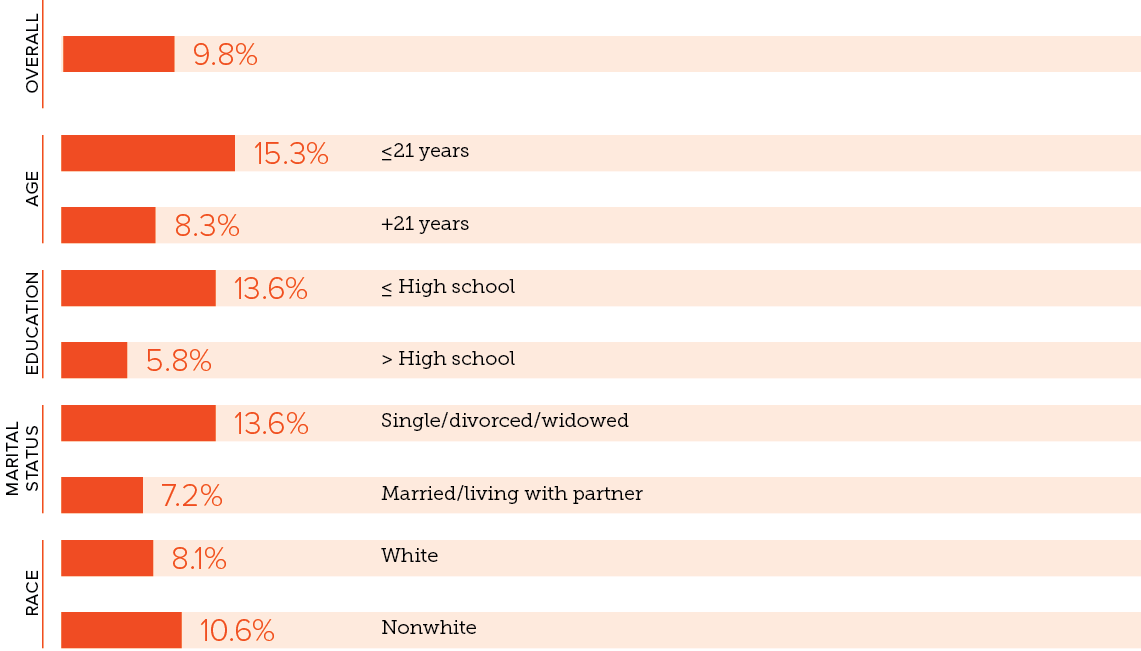

- In Shelby County, 5 percent of mothers of 12-month-olds reported symptoms indicative of depression, and nearly 10 percent of these mothers had possible depression (i.e., just under the threshold for depression). Mothers who were younger, single, had less education, or were nonwhite were more likely to be depressed (Figure 3.4).

Source: CANDLE Study (2009–2014) Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) at 12-month visit , percentage who met cutoff (10 or greater) for possible depression

Social Support can Help Both Parents and Children.

It is important to have people you can count on for support, particularly when dealing with stress. Social support can reduce the emotional distress of the parent, and help improve the quality of parent-child relationships.

When support and encouragement is given to those caring for a child, adults are better able to be responsive and nurturing parents. Social support— both from trusted medical professionals and from less formal networks, such as friends, family, and a faith community—help reduce the stress that comes with raising a child.

Through providing parents with increased opportunities to complete school or job-training, or connecting them with local resources to address their own health, providers can utilize a more holistic approach to strengthen the family’s well-being by addressing parents’ needs, thus enhancing parent-child interaction, and in turn, children’s development.

Conclusion

The development of social and emotional skills depends heavily on the experiences that children have in their home. Children can thrive with regular, positive, parent-child interactions. While parental stress and mental health concerns can jeopardize these interactions, mental health treatment and general social support of parents can alleviate some of the stress and strain of raising a child. This, in turn, will enable parents to focus more on their child and provide a warm, nurturing environment in their home.

- Vogel, C.A., Boller, K., Xue, Y., Blair, R., Aikens, N., Burwick, A., et al. (2011). Learning as we go: A first snapshot of Early Head Start programs, staff, families, and children. OPRE Report #2011-7, Washington, D.C.: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Heckman, J.J. (2006). Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science, 312(5782), 1900–1902

- Morse, S.B., Zheng, H., Tang, Y., & Roth, J. (2009). Early school-age outcomes of late preterm infants. Pediatrics, 123(4), e622–e629.

- Cepeda, I.L., Grunau, R.E., Weinberg, H., Herdman, A.T., Cheung, T., Liotti, M., et al. (2007). Magneto-encephalography study of brain dynamics in young children born extremely preterm. International Congress Series, 1300, 99–102.

- Figlio, D.N., Guryan, J., Karbownik, K., & Roth, J. (2013). The effects of poor neonatal health on children’s cognitive development. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Phillips, D.A. & Shonkoff, J.P. (2000). From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. National Academies Press.

- Moore, K.A., Redd, Z., Burkhauser, M., Mbwana, K., & Collins, A. (2002) Children in poverty: Trends, consequences and policy options. Child Trends, 2009-11.

- Eamon, M.K. (2000). Structural model of the effects of poverty on externalizing and internalizing behaviors of four-tofive-year-old children. Social Work Research, 24(3), 143–154.

- Yeung, W.J., Linver, M.R., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2002). How money matters for young children’s development: parental investment and family processes. Child Development, 73(6), 1861–1879.

- Sklar, C. (2010). Charting a new course for children in poverty: The reauthorization of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Program. Washington D.C.: Zero to Three.

- Davis-Kean, P.E. (2005). The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 294.

- Carlson, M.J. & Corcoran, M.E. (2001). Family structure and children’s behavioral and cognitive outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(3), 779–792.

- McLanahan, S.S. (1995). The consequences of nonmarital child-bearing for women, children, and society. Report to Congress on out-of-wedlock childbearing. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Kaye, K. (2012). Why it matters: Teen childbearing and infant health. Washington, D.C.: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Massachussetts: Harvard University Press.

- Sabol, T.J., & Pianta, R.C. (2012). Patterns of school readiness forecast achievement and socioemotional development at the end of elementary school. Child Development, 83(1), 282–299.

- Raikes, H.A. & Thompson, R.A. (2006). Family emotional climate, attachment security and young children’s emotion knowledge in a high risk sample. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 24(1), 89–104.

- Rice, K.F. & Groves, B.M. (2005). Hope and healing: A caregiver’s guide to helping young children affected by trauma. Washington, D.C.: Zero to Three.

- Cummings, E.M., Schermerhorn, A.C., Keller, P.S., & Davies, P.T. (2008). Parental depressive symptoms, children’s representations of family relationships, and child adjustment. Social Development, 17(2), 278–305.

- Elgar, F.J., Mills, R.S.L., McGrath, P.J., Waschbusch, D.A., & Brownridge, D.A. (2007). Maternal and paternal depressive symptoms and child maladjustment: The mediating role of parental behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35(6), 943–955.

- Goodman, S.H., & Gotlib, I.H. (1999). Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review, 106(3), 458.

- Lim, J., Wood, B.L., & Miller, B.D. (2008). Maternal depression and parenting in relation to child internalizing symptoms and asthma disease activity. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(2), 264.

- Lovejoy, M.C., Graczyk, P.A., O’Hare, E., & Neuman, G. (2000). Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(5) 561–592.

- Gaynes, B.N., Gavin, N., Meltzer-Brody, S., Lohr, K.N., Swinson, T., Gartlehner, G., & Miller, W.C. (2005). Perinatal depression: Prevalence, screening accuracy, and screen- ing outcomes. Evidence report/technology assessment (summary), 119, 1–8.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. (2011). Early Head Start Research and Evaluation (EHSRE) Study, 1996-2010 Ann Arbor, Mich.: Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research.

- Shaw, D.S., Owens, E.B., Giovannelli, J., & Winslow, E.B. (2001). Infant and toddler pathways leading to early externalizing disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(1), 36–43.

- Latimer, K., Wilson, P., Kemp, J. Thompson, L., Sim, F., Gillberg, C., et al. (2012). Disruptive behaviour disorders: A systematic review of environmental antenatal and early years risk factors. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38(5), 611–628.

- Manuel, J.I., Martinson, M.L., Bledsoe-Mansori, S.E., & Bellamy, J.L. (2012). The influence of stress and social support on depressive symptoms in mothers with young children. Social Science & Medicine, 75(11) 2013–2020.